Digital&Dead interviewed

by Wade Wallerstein

Introduction

A recent study published by the University of Oxford Internet Institute reported that within the next 50 years there will be more dead users than alive users on Facebook. If you think about it, this makes sense: once hot platforms lose steam, stop growing, and users lose interest. Early adopters grow old, get sick, and pass away, leaving behind static profiles whose stored interactions become like ghostly ectoplasm trails. This is all pretty new—the Internet hasn’t been around for that long, and social media is even greener. Nobody really thought about what would happen to the internet as a once young generation phased through its organic life cycle. It’s jarring to visit internet cemeteries like MySpace or GeoCities, which are becoming increasingly difficult to access as these once bustling digital metropolises fester away on long forgotten servers, somewhere.

There is a popular belief that once you post something on the internet, it’s there forever. Digital death evokes a slew of logistical and ethical issues. Who has rights to the data of the dead? What happens to these dead profiles? How do we grapple with individuals’ right to be forgotten, or rather rest in peace. And what will the landscape of the internet look like when it’s littered with more dead profiles than live ones? As the internet grows from infancy to toddlerhood, a new epoch will arise that netizens of the world might not know how to grapple with.

Enter Digital&Dead: a two-woman collective comprised of London-based artists Sarah Derat and Rachel McRae. These artists, whose studio practices are quite different, have joined forces to practice a new kind of multidisciplinary engagement that seeks to understand how the relationship between death and technology is changing the shape of digital culture.

In the past, Derat and McRae have experimented with augmented reality as a tool to parse virtual death over the actual world. Their virtual sculptures, which can be viewed through a special app designed by the artists, stand as hybrid monuments that capture new forms of memorialization made possible by the digital. More

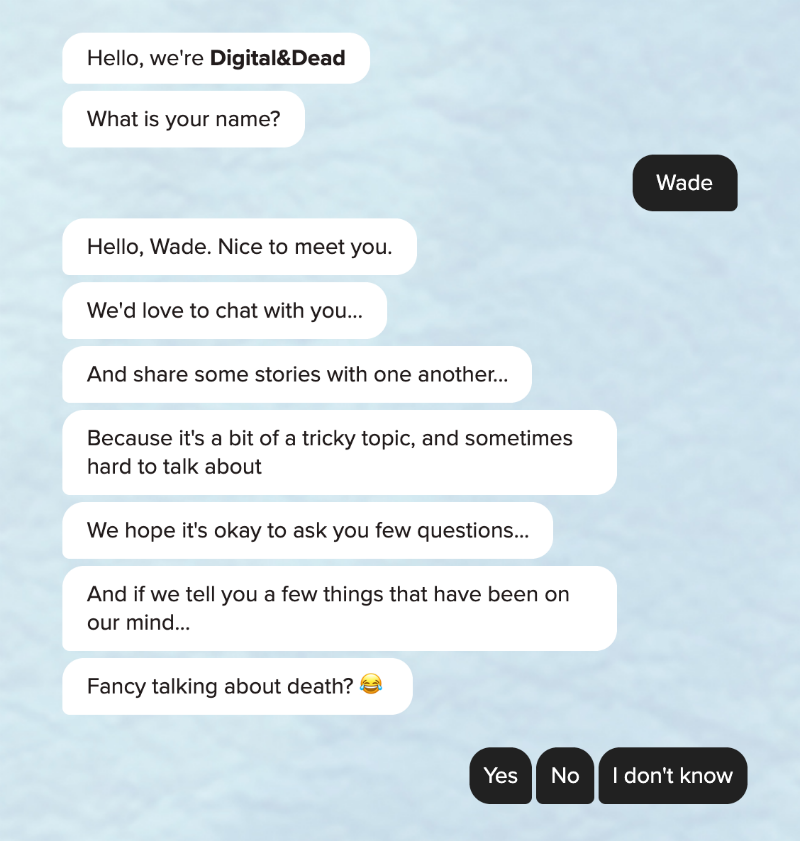

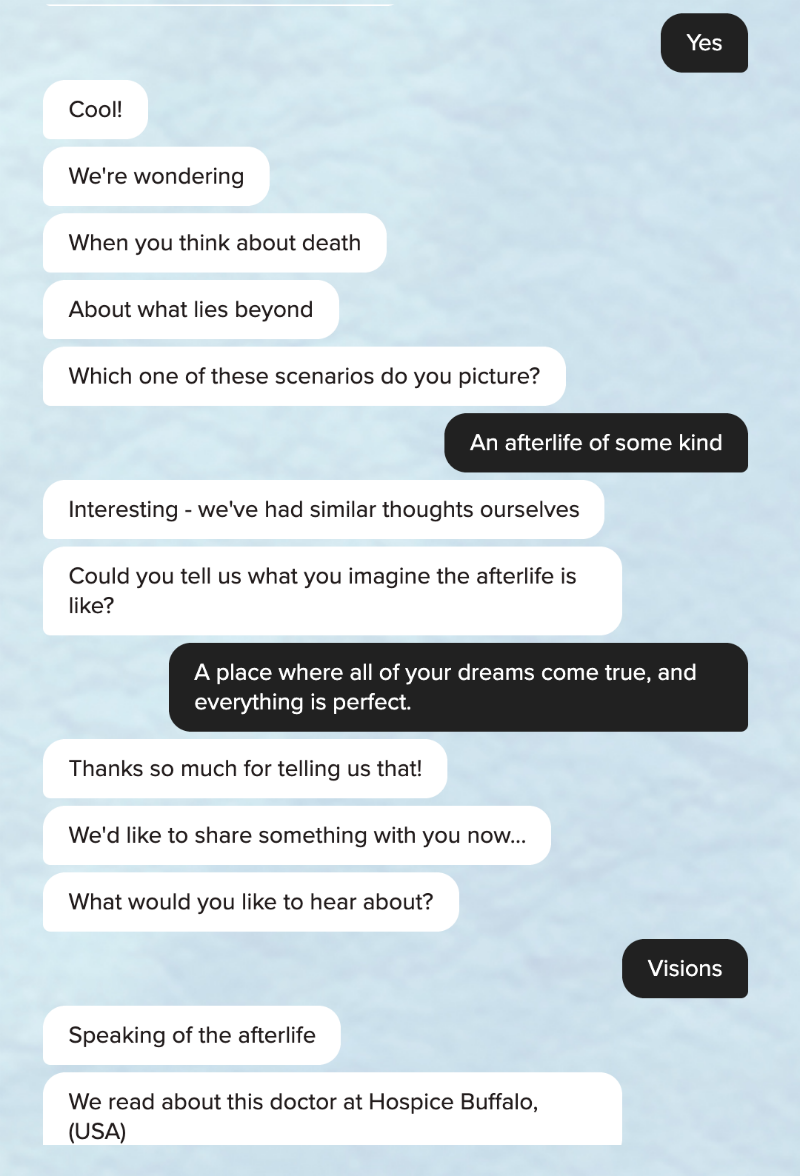

More recently, Derat and McRae completed a residency at SPACE Art + Technology in London, in which the pair attempted to create an AI bot version of themselves that might immortalize their consciousnesses in a combined assemblage of hardware, software, and data past the demise of their organic bodies. The resulting chat bot is a combination of both artists’ personalities that can talk to users about their experiences surrounding death, both asking questions and sharing intimate stories pulled right from the artists’ personal memory banks. Part research device, part therapist, and part exploration into how the uploading of consciousness might work in the future, this bot urges emotional engagement and deep thinking about the nature of death, the nature of humanity, and how AI is shaping the way that we see the world.

Fresh off of the heels of this exciting experimentation, I caught up with the famously morbid duo to talk about how they see digital landscapes changing in the wake of rapidly transforming technologies.

Interview

Wade Wallerstein: To start us off, tell me about Digital&Dead? What are your aims and your goals, and what kinds of projects have you done in the past?

Rache McRael: In terms of key interests what we’re trying to do is approach the topic of death and digital legacy or death and life extension where it meets technology in a way that’s holistic. We’re looking at these topics from the perspectives of theology, spirituality, magic — these kinds of world building/cosmological belief systems and exploring how technology is involved in them. We’re also dealing with pragmatic issues, so looking at the way that legal ownership plays into it, or misgendering…you could almost call it the pragmatics of real world problems that you face from a legal standpoint. We’re also interested in interpersonal stories and people’s experiences, so having interactions with folks, hearing about their actual problems, their feelings. It’s spiritual, it’s academic, but it’s also very much about how people feel because death touches everything.

Sarah Derat: Like Rachel said, our approach is really about being multidisciplinary in a nonhierarchical way. We’re really interested in going full spectrum from ethics to neuroscience, artificial intelligence, anthropology, ethnography, while still thinking about the impact on people’s mental health.

WW: You’re dealing with these things on a very human level—really thinking about not just what this technology is doing to society as a whole but rather on an individual human level by asking how these things are affecting all of us, our daily lives, who we are, and our consciousnesses. This really stands out to me about what you’re doing. You recently had a Residency at Space Art & Technology, I was hoping that you could take me through what the project was and how it culminated.

RM: The Space Art & Tech Residency, the focus was on artificial intelligence. We sort of knew that this would probably be step one in a process. We were really interested in potentially creating versions of ourselves that would live on after we died. We were interested in the process of the preservation of the self or the versioning of the self through artificial intelligence, and, again, looking at it from a very broad, holistic way. As were were working through this process I think the learning curve involved in something like this, and the limitations in technology and the pragmatics concerned that come along with preserving or versioning the self online, really started to key in in various places. Dealing with this became a bit of a difficulty, and we thought, shit, how do we approach this? And how do we do it in three months? What’s the most effective that we can approach AI initially? Well we ended up deciding that that’s through a bot, specifically a bot that can gather information for us— not necessarily to replicate some of the experiences and the conversations we were having in our live events, but to sort of sit next to it, as a way of gathering information.

SD: The chat bot we produced is a very interesting transitional tool, both conceptually and formally, into this subject. Going from augmented reality towards machine learning and AI, it really is the perfect middle ground for this and helped us in laying the foundations of our research. Because it collects anonymized data, it’s also an interesting point of exploration for us in itself. Simultaneously, it emulates the public events that we’ve done in the past which were open conversations with different types of audiences. All of them were pretty mind-blowing to be honest. We both have vivid memories of our talk at The South London Gallery in 2018. We quickly realised after making our AR piece in 2017 that the work had somehow become an empathic platform. People we met during our past exhibitions have always quite easily shared some of their personal stories in relationship to dying or mourning online - so retrospectively, it made sense to create a tool able to keep the flow of this ongoing conversation open.

WW: Something that you touched on there is that this is a first step, laying the foundation, and the technological difficulties that come into play when archiving the self, preserving the self, and versioning the self. What would you identify as those key issues that prevent people from tapping into this world? What sorts of roadblocks did you come across as you were trying to build this AI, and create a model for how we might be able to archive ourselves?

RM: First off there’s a massive learning curve when it comes to the actual technology itself—learning how we can go about this, how we can replicate language and the way that language works, especially English. Though, I think that regardless of which language you speak, it can be really hard to build a bot that responds and speaks in a way that seems natural and seems human; or at least a bot that generates its own responses. That’s really fucking difficult. But also trying to figure out how to mimic a human being —that’s a whole other thing. That’s like think tank-level research.

SD: And especially afterwards, are we talking about versioning or preservation? What sort of preservation are we talking about? Is it an upload? Is it a version? Each makes the subject and end result totally different, both technically and in terms of content and how it’s treated or handled. If you go beyond the basic ethical questions, there’s philosophy involved, there’s your own system of belief, etc. Plus, Rachel and I were talking a lot about memory formation and how the field of neuroscience, to this day, is still not certain about how memories are formed in the brain. How can we upload or fully preserve something that we’re not fully understanding? The brain is both chemicals and electricity…it’s not simple. Should we only consider the brain as the sole part of the body that would be worth versioning? Is all we really are only located up there ? I guess It’s more about attempting to make a copy, or a version. And if so, what is this version going to be? How is it going to move? Option 1: is it going to evolve while you’re still alive? I was reading a couple of months ago an essay focused on the legal issues raised by having fully-functioning AI versions of ourselves while alive. There was a paragraph advising that, if we were to develop such AI entity, we should grant them a minimum of five years of limited autonomy to watch them evolve and provide them with a legal status similar to the legal status of a teenager. But Option 2—and probably the one we’d end going for—is of course to think about an upload post death...

RM: And when does it stop on the death bed being the other thing. Your brain goes through some pretty scary slash magical shit when everything’s shutting down. That’s a whole experience unto itself. Presumably if we’re thinking about talking with someone post-death, we’re sort of imagining like a ghost of sorts, or a spirit….are we going to talk to someone after that happens? Will that affect it? Do we have it feel pain? Do we have it feel the strange dopamine rush…you get a lot of happy hormones to calm you down as you’re dying. When do you stop hitting play?

WW: Sarah, you were talking about memory formation, and what that means and what memory looks like when you’re able to upload versions of yourself to the internet. Earlier, Rachel, you mentioned the concept of world building and how death and death practices contribute to concepts of world building. What kind of world do we build when we upload versions or copies of ourselves online, and what does that world look like? Also, how does memory and the way that we form memory contribute to this world building that digital technologies are assisting us to do?

RM: I’ve recently been involved in discussions about how cognition requires movement. The process of moving through spaces is a process of thinking, hugely! I think that you’re right, this idea of the terrain and the materiality of the place where the bot lives is hugely important. That’s where it’s going to be moving, that’s where it’s going to be learning. There’s an article that I wrote with a friend of mine…the folks at the Pirurvik Centre for Inuit Language, Culture and Wellbeing in Nunavut, Canada needed to come up with a word for the World Wide Web, the Internet, and a word for moving through them. The word they decided on, Ikiaqqijjut, was a word that applies to a particular Shamanic practice, and it also means ‘moving through layers.’ It has to do with this idea of a shaman moving through an external landscape, looking for an answer, while their physical body stays in the same place. The bot version of yourself is going to be doing something like that, presumably. But then again, the weird thing is we’re now gonna be at a double impasse because we don’t entirely understand—as a casual user of the internet or even someone who’s well-versed in how networks function—how the digital works. If we don’t have an idea of what the landscapes gonna be like, and we also don’t know how the meat works, then what are we making? It’s weird, it almost turns into another kind of afterlife mystery.

SD: It really is a shot in the dark isn’t it.

WW: That’s fascinating to compare how our bodies work and how the internet works to thinking about what happens after death. You’re right, there are always going to be factors in any technological landscape that are obscured from us. The way that machines think for example, the way that they perceive things, are functions beyond human comprehension.

RM: And also I firmly believe that some of the most interesting discussions about this kind of topic are coming from indigenous academics and people who are looking at re-indigenization. I think there’s something about—you don’t even need to go towards animism, but this idea of embodiment, the body, and then tech and the internet being both a place and a thing that is simultaneously dematerialized and material…there’s something to that. But again all of this complicated stuff, the ethical and legal part of it, it means that approaching this idea of digitizing yourself will require a lot of work—there’s so much preparation involved in it, there’s so much thinking.

WW: Almost like the embalming of a body, like mummification, a ritual practice. When you mummify someone you extract the brain, you take out the organs and put them in jars. It’s almost like when you’re creating an AI: you are distilling all of these different functions of humanity, putting them in different places, plugging them into different algorithmic environments and having them all come together in this condensed mummified version of you. I don’t want to say mummified because that implies that the AI is flat or dead or stored away when in the case of your AI it’s still functioning and working and still interacting with people. It almost reminds of Chinese cosmologies and concepts of ‘ghosts’ and how ghosts are not just spirits that haunt you, but instead your relatives; your ancestors that are around you all the time and continue to interact with you all the time on a daily basis.

Before we keep talking about this landscape and what it looks like when it’s populated with bots and versions and copies, I want to talk to you a little bit about the AI you created itself. Talking to it is pretty eerie, it has such a depth of personality but it also really invites a strong emotional response. The emotional affect part of the bot is something that I find really interesting and I think is really relevant to conversations about technoid landscapes because there is an emotional aspect there. So, tell me a bit about this bot and the details that she includes—who is she? How was she formed? How does she function? What has been the product of her genesis?

SD: I think it was clear to us that when we decided to do this bot that it was going to be a “we”—it was going to be the hybrid version of both of us, and that it would share some personal stories. We just refused the idea of having an ‘I’. It was clear to us that you cannot expect people to share anything on such a sensitive topic without going through the same process yourself. This economy of sharing was really one of the first things we put down on paper as one of the obvious goals of the bots. The bot is doing its job and we’re really happy about it and in the end it’s probably gathering more than we anticipated.

If you think about the history of chatbots, they’ve always been quite confessional. There’s something about this idea of sharing something to a machine, maybe because it’s easy to imagine that a bot is—rightly or not—non-judgmental. I’m interested in the history of bots and their connection to psychology. If you think about Eliza—one of the first ever chatbots—it was meant to be a therapist. It’s quite funny to see that the technology comprising bots has not changed that much in 50 years. That being said, it’s only in the past few years that they have boomed and taken such a prevelant place in our digital interactions. There’s a real desire in trying to anthropomorphise tech and having a form of human-like interaction—I mean you just have to look at people using Alexa, and the way they talk to it.

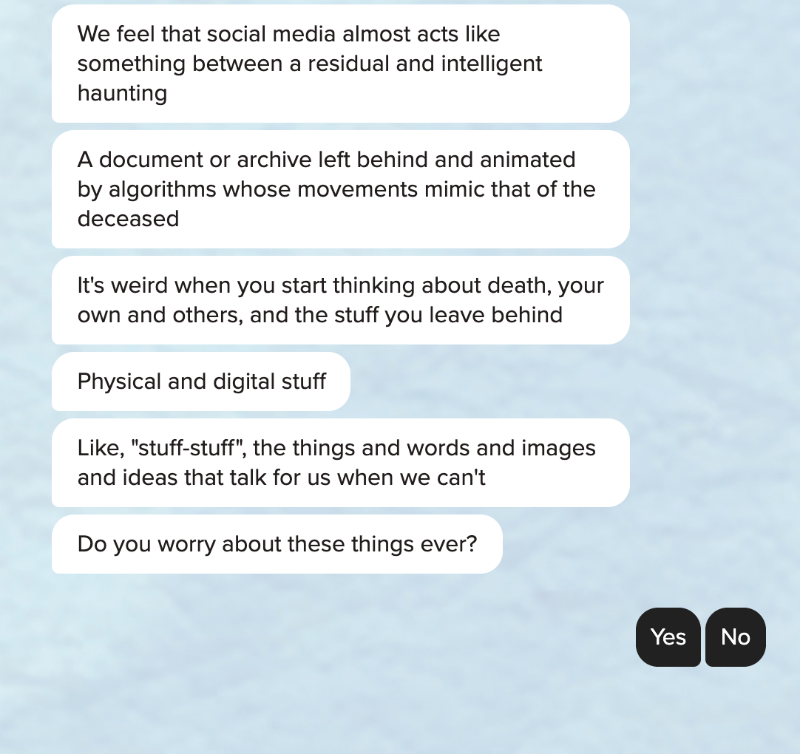

We approached this phenomenon in an ethical way. From a technical and practical point of view, we formatted the bot in a way that was meant to be very conversational. We really looked carefully at the way that we exchange on Messenger, and so we split the dialogue in to different bubbles; in fact, there are a lot of things, including typos, in terms of replicating the way that we talk, the manners of speech that we both have…something to give some real body, some realness and authenticity to the chat bot.

WW: You talk about Eliza and these bots being functional, as having a purpose, and employing them to do the work of a psychiatrist or a friend. You also mentioned the economy of sharing. There seem to be two things going on here: you have your bot and its functions, but it’s also connected to this economy of sharing that’s very human and that we are all being enlisted in—not just for our data but also for our sharing services. If you think about any of biggest tech projects, crowdsourcing plays a huge role. Google Translate, for example, allows you to contribute to its language database through suggestions or corrections—crowdsourcing knowledge and monetizing participation. I’m thinking about this economy of sharing and how new kinds of e-laborers—Uber drivers, Deliveroo drivers, online customer service representatives—are human beings that are being recruited for automated functions. But then bots being recruited for these purposes as well.

What does a socio-economic internet landscape look like? Are our versions going to become slaves in a way? I hate to use that word out of historical considerations, but are they going to become indentured to some corporate purpose? Im curious as to how this landscape is being changed by the need to collect data and the sort of labor that’s involved in doing so. How do bots fit into this paradigm?

RM: I think in terms of our own bot, even though we are technically mining anonymized information from our audience, it was important ethically for us to share some vulnerable stories of our own, and actual fears of our own, in a kind of give and take. It’s really easy to make a bot that can coerce you into just giving up information, but it’s not necessarily ethical. In that case, then the bot is just like any other bot, you know what I mean just sort of taking stuff from you. If we’re looking at it within a transactional framework, we want there to be give and take on both sides. This can be accomplished in terms of even asking people “what do you want to talk about” “here’s a story that might be applicable to something that you’re interested in.” We are gathering information, anonymously, but we are gathering information—yet we are still giving out some stuff of our own that’s pretty raw.

You have to trust us, there has to be a certain amount of good faith that what we’re saying is true, but then it’s the same from their (the participant’s) side as well. I think that we’re trying to think of this as a different kind of bot experience. There are two main kinds of bots: those that try to gather information, and those that disseminate it. We’re trying to do both in a slightly more direct and personable way. There was this story that a friend of mine told me—there’s a certain sort of naming protocol that comes into play in Australian aboriginal death practices. When a person dies, they stop saying their name. In certain groups, you go farther than that— you don’t say their name, you also change the words you use for their occupation or words that are directly related to what they did in their life. Because we’re talking about fairly tight knit groups, that kind of linguistic change is possible. All of a sudden, if you think about that sort of information getting hoovered up by the internet, getting scooped up by Big Data and used in things like self-driving cars, it’s like fucking purgatory. Are you stuck? How long are you stuck?

SD: The idea of privacy, and the absence of privacy post death, is something that we’re really interested in. The EU has introduced a “Right to Be Forgotten” bill but it only applies to the living, which I find quite ironic because I can easily see why someone would like it to be applied to someone’s data post death. Big corporations are making so much cash off of us, I can’t see why they wouldn’t do the same using our data post death. I mean, when from their perspective it’s pretty obvious that any opportunity to monetize is a good idea. If you look at post-death privacy policy in law on an international level, they’re non-existent. Countries and governments in power deal with issues on a case-to-case basis rather than trying to think about the problem at large.

Also, it’s interesting that Rachel brought it up aboriginal practices death practices because when we are thinking about the current tech landscape, we’re truly talking about a landscape that is a Christian landscape. An English-speaking white Christian landscape!

RM: Fucking colonial as fuck!

WW: Absolutely! I’m glad you brought this up because I think this is a great time to talk about the religious terminology embedded within technology discourse. Whenever we talk about AI, we use words like “godlike.” It’s like we deify these subjects. As you’ve explained, all of your research has been coinciding with religious practices from all different kinds of groups in terms of how they deal with death and the ritualization surrounding death. So how have you guys been grappling with these ideas as you’re dealing with the ‘godlike’ potential of AI? How do these ideas of a religious fervor or a religious undertone to these kinds of projects affect the way that you’re working or thinking about creating an AI bot?

SD: Well, technological progress historically has been intertwined with something that has to do with magic; a god-sent miracle or whatever you want to call it. We don’t have to go back in time much to notice it. Just look at the advent of electricity…I was listening to a podcast the other day about a French Literature movement called “Merveilleux Scientifique”, which could translate as “marvellous scientific”. It thrived at the peak of the Industrial Revolution and preceded what we call now Science Fiction. Anyway, the Merveilleux Scientifique shows a desire to look at science and tech as something extraordinary, enchanting, somehow magical.

But to go back to AI, we probably have to make a distinction between the way we—as users—describe AI and tech in general and the way people who build AI and tech systems choose to describe and name them. It’s a pretty human thing to associate something we don’t fully understand with some sort of spiritual, esoterical, god-like vibe. I mean, it’s not a bad idea, naming a thing is the first attempt at understanding it. Plus, Silicon Valley companies make sure everything remain quite obscure, right? The problem lies more in the way the corporations making the systems we use every day use religious terminology and references to market them.

RM: It goes back to this thing that Sarah and I talk about a lot with the first Digital&Dead project that we did—the augmented reality one. The spiritualist movement was obsessed with electricity and the telegraph. It was the idea that energy was zipping unseen through the air and then that got tied in with this whole idea that, well, if energy is zipping through then the ghosts must be zipping through too; and then we can channel that in the same way that we can channel and draw electricity now. The project we made, this was part of the concept—that you have ghosts in the wireless waves floating around you. Dr. Elaine Kasket—she brought this up recently when we were having a discussion with her—there’s an idea of eternity in the internet or eternity in your digital legacy. All of these websites, like eterni.me, etc., even outside of AI and just on online memorial sites, the Judaeo-Christian notion that a heaven-like eternity that’s just like you, forever, is so pervasive. To be honest it’s more like your continuation, or your ability to continue to exist, is ancestor worship. Something between ancestor worship and archiving at least. Once people stop caring and once they stop hitting that refresh button or putting you on the next bit of hard drive, as soon as the desire to preserve or replicate or version goes, you go pfffff. You’re potentially dead in a whole new way.

WW: In this process—whether you’re alive or dead actually and then transitioned to an online embodiment—what happens to your consciousness as it becomes infused in digital environments? With the upload or the versioning of the self, how do circuits and hardware affect our consciousness and then continue to effect it as it becomes executed algorithmically?

RM: I think it’s really personal. For me, this is one of the things about this whole idea of uploading or versioning that I’ve been trying to wrap my mind around. The whole time we’ve been doing this project, once we started talking about it, I’ve been trying to wrap my head around how that would work or what that would be like. The only thing I can possibly align it to—and this goes back to what Sarah was saying about memory and memory formation and how we don’t really understand—we have some idea of how it works, you’re shedding yourself all the fucking time. Your brain is very plastic, and your memory is not a direct recording. I wonder sometimes if—as a thinking moving meat form shuffling around in space—you’re not cognitively versioning all the time. There’s something scary, something truly frightening about this idea of you almost giving yourself to the computer. But you, this physical you, not going with it, that’s kind of scary but for all I fucking know I’ve left innumerable numbers of me behind and that’s not fucking with my shit right now. Maybe it should be, but it’s not so I don’t know.

WW: You said that you “might” have left all of these copies behind but I don’t think it’s a might: you did. There are programs now where if you sit on a website for three minutes the algorithm can tell where your eye has been on the page and from that information predict exactly what you’re going to buy, when you’re going to buy it, and how you’re going to buy it. We’ve gone beyond just data mining—it takes very little data to predict exactly what you’re going to do. Regardless of conversations about death or consciously versioning yourself, it’s almost like every action that you take online inadvertently versions yourself just through your action. I think that’s a key aspect of any contemporary technoid landscape that people don’t understand or talk about in much depth. It’s not just the conscious decisions to create a version of yourself, it’s not just the screennames you create, it’s every single click that you do, every page that you scroll, the time that you spend scrolling. It’s inadvertent versioning, inadvertently creating copies of yourself.

SD: Yes, expect that you’re not being openly told how extensive and incredibly detailed this inadvertent versioning is.

WW: What kinds of landscapes are created with all of these versions of ourselves existing online? What does that environment look like? We talked before about an “archive cemetary” and the zombification of the self. With all of these dead identities floating around, what do you guys see the internet as shaping up to be like?

SD: That’s such a dense question. There’s no right or wrong answer. I would probably tell you a different thing in two weeks from now, depending on what’s going on in the world. My main concern with talking about technological landscapes is “who are the main players of this landscape?” And who’s behind the code? Who’s behind the technology and how it’s handled and how it’s disseminated, and how does it affect people? I worry about the racial and gender biases buried deep inside code lines and how much they affect us. I am concerned about being part of a technological landscape built without empathy. To go back to the tons of data we create which end up floating around, I’m thinking about how much of a problem it is and will keep on being with mounting climate change. Quite ironic to think that the tech landscape is a growing threat to the IRL one…

WW: I think that this idea of capitalization is the key to these conversations because a lot of the versioning that’s happening is directly related to commercial data mining. As I said, corporate interests want to figure out who we are and how they can better sell to us. Or not even how to better sell to us but how to better capture our attention. You look at YouTube’s recommendation algorithm and how it recommends more extreme content for you based on your interests so that your eyes stay glued to the screen for longer and you watch more advertisements.

SD: Or pushing you into watching something…My boyfriend and I have recently noticed that Youtube keeps on trying to make us watch Jordan Peterson videos. We’re like, fuck this shit.

RM: Earlier I was talking about the idea of how you process information by movement, by moving through things. It’s a relational procedure. So you have a few different things at play: there’s the data, there’s you, there’s your browser, and then there’s the place where the data’s being stored and how it’s being processed. There’s such a complex back end that you didn’t necessarily have with early internet. It’s like Sarah was saying, there are people that are hosting this data and the back end of that is controlling you. There are ways of circumnavigating or getting around it—adblockers, VPN bouncers, TOR browsers, etc. You can sort of hack it, but it becomes a problem when the providers are monolithic like that. It’s like being in a small town that just has Walmart. It’s a big box store. It’s not like you even have the mall anymore, like the American, quasiutopian idea of the mall as the town square and the shopping center and the church. Now the internet is like a big box store but people are starting to get sick of that. It’s kind of a wild west beyond the store walls. But when your entrance way and your closet and your bookshelf and all of your storage places are all in the same spot, but that spot is also where you order your food from and also where you watch your entertainment and also where you talk to your family, it becomes a big box store sort of landscape.

WW: So do you guys feel like there are ways to change this landscape? Are there ways that we can take control of—I don’t want to just make this conversation about data because I hate when people are like ‘omg my data this, omg my data that’ and I think that’s a really low level way to talk about it. I think we should be elevating the conversation to talk about ourselves because data is just a component of the self at this point. So what happens to the self when you’re subjected to this kind of monolithic, homogenizing environment. Are there alternative models? Are there other ways to do this or to version the self and participate in these kinds of archiving modes that are outside of that? Or is it not possible?

RM: There’s a feminist scholar, we used to love her but then things got problimatic, Nina Power (there’s been some professional alignment with TERF’s) —she has an argument about feminism that goes after certain sorts of consumer aesthetics. So it’s like, “ I’m gonna criticize this sort of aesthetic,” but then before you know it that particular problematic aesthetic is no longer in fashion, it goes away, and another one appears in its place. You end up in a weird way angirly chasing this Capitalist production over and over again, and because of that you get locked in a cycle of trying to create a subversive critique; but then it gets commercialized and co-opted. New subversive modes are going to be constantly created that are then appropriated. Like punk imagery being appropriated by Capitalism. There’s a similar thing with tech. If we come up with a way of circumnavigating this bullshit, is Google going to buy it out from under us anyway? That’s always the fear.

RM: Even in terms of the nice stuff about it—like Instagram being a thing that had a linear flow for a while, and then the Facebook algorithm comes in—there’s no difference between me talking to my audience on Instagram and me taking to my audience on Facebook. It’s all going to be sorted in the same way anyway, there’s no difference. But I also don’t want to think that it’s always going to be like that because then why do anything?

SD: I agree. I think people are getting more aware of tech tricks and biases by the day. It never used to be in the news daily. So that’s a good thing. Like Rachel, I want to think that we can and will do better by being inquisitive and holding tech companies accountable.

WW: One thing that I always want to be clear with the universe about is that THIS IS NOT NEW! Think about when you used to go to the grocery store and get coupons based on your purchase history. That totally predated computers. People weren’t freaking out when they got a toilet paper coupon after they just bought a sixteen pack of 4-ply. People weren’t thinking about it like that. If you think about TV, they do studies and they monitor what people watch and they change advertisements based on that and that also totally predated the internet. I wonder, why do we care about this now? Why didn’t we care about this fifty year sago? Is that because it’s more obvious? Because our social functions are more closely integrated into these environments? Is it because, as you said Rachel, all of these different things are coming together in one place that we finally feel like it’s an issue?

To me, all of the things that cause people to go “oh em gee they’re using my data! It recommended me something this sucks” is kind of bullshit because I personally fucking hate it when the ads don’t match my interests and I love it when they give me something that I want. I love it when Google knows exactly what I want to search for and it’s instant. It’s like this battle between “I want privacy” and “I want better services.” And that’s how it’s always been—people wanted coupons that matched their buying so that they actually saved money. Yes I’m nervous about what’s going to happen to my body and my consciousness after I die yet I do want to live on. How do you deal with that tension, that back and forth between wanting the better service, wanting to be archived, wanting to create a better version of yourself, while also dealing with the negative impacts of what that means?

SD: God that’s a really fine line to navigate. I don’t think the response is the same in terms of your legacy and the way you do online shopping.

RM: It also probably depends on the day that you talk to us. Have I been pissed off because I’ve been trying to watch something on youtube and I keep getting interrupted by Godzilla adverts? Yes and no.

SD: We care more about how our data are handled precisely because in the past, they did not really play against us. One of my mates is working for a company dealing with the fine tuning to maximize your Tesco coupons. Well my friend would not recommend you to use your Tesco bank card and our Tesco point card—whatever it’s called— because if you were to buy quite regularly cigarettes or alcohol and then request a mortgage, well things could get complicated.

In terms of this fine line between better service and not giving away your entire credit history or whatever, there are solutions that can be implemented but they’re not really pushed forward because there’s a clear agenda behind keeping the most accurate record of yourself. Another friend of mine is working for a company that basically create secured windows to process a transaction at a given time and date. It acts as a middle person between you and the company you want to get something from. Only the data you need to perform this transaction will be used and then it’s gone.

Concerning the idea of legacy, that’s a very hard question.

WW: I mean I think it’s the question that encompasses your entire practice, I don’t expect an easy answer.

SD: You know the topic of digital legacy and the use of tech such as AI applied to digital legacy is still very speculative. In our research, we came across many digital legacy companies whose services are yet to be launched. Why is that? There might be something similar to the history of VR: people not being into it back in the 80’s and finding it plain weird. Also it has to do with crazy tech expectations we have not accomplished yet. We’re projecting a lot on AI.

RM: It’s also what’s profitable too.

SD: Right! I don’t think the tech is ready yet and even if it was, it’s deffo not profitable. Otherwise, it’d be out there already. Also, death, legacy and the digital age is not new. We’ve all been on these terrible-looking online cemeteries, the one that look like the first website you ever visited in the late 90s. They’re dead right, nothing’s going on on them.

RM: They’re like actual neglected cemeteries — overgrown, glitchy, full of fuckups, no one is grooming them.

WW: That’s an amazing way to think about this that we haven’t touched upon yet in relation to technological landscapes: the dead zones. If you are a digital legacy, what happens in terms of how technology advances and inoperability down the line as hardware becomes unable to run higher levels of software and programming languages become more abstract? I think that dead zones are an iconic landmark in any technoid landscape—the zones that kind of exist in a server that you can kind of access but not really. I think of artists like Cameron Askin who works to archive and preserve GeoCities websites. Those are dead zones, but he’s been using the Internet Archive and tools like the WayBack Machine to archive and bring these dead zones back into relevance. I think that this is crucial to conversations about digital legacy. Yes I’ll exist online forever, but at what point are they going to forget about me and relegate myself to one of these digital cemeteries?

SD: That’s super interesting because I think there’s an interesting labor at play here—a different sort of ‘labor of love’ in a sense. If you think about the way we dealt with memorialisation in the past—going to a cemetery, building shrines, holding funerals—we were laboring trying to preserve a memory of a person. When you think about artificial intelligence, it’s the other way around. The undead pokes at you to be preserved. They, or it, or whatever it is, is activating this.

RM: That goes back to this whole idea of our wanting to perform ancestor worship and then also having whatever mediating factor be able to read this shit to begin with — you need a translator, you need an archivist, and you need someone with the desire to keep the thing going and to provide you with a way to get through this thing. If the bot still functions, if the AI still functions, and it’s locked in—or it’s in a dead zone, or its mutilated and half in a dead zone, and unable to speak because its metaphorical tongue’s been metaphorically severed, you know? A friend of mine who’s doing a film about the similarity between bots and witches familiars has been palling around with these people who are the top of the AI game for the past year or so, and what she told me is that a lot of the focus that these AI developers have been putting their time and effort into has been bots—scripted, interactive bots—which I was not expecting. A lot of it had to do more with this idea, not necessarily of what we would think of as an autonomous entity roaming freely, but rather a responsive service provider that could give you the user an experience. It had less to do with consciousness trapped-in, or what we would consider conscious or thinking, even though its performing some of these acts.

WW: Just to clarify, you’re saying that from her bot research people aren’t thinking about creating consciousness but about creating services instead?

RM: Like what you would think of traditionally as a bot, a thing that is there and there to talk to you. If we were actually thinking about “real AI” it could tell you to fuck off or it could do that really terrifying thing like those two AI’s who built their own language to talk to one another and pfft, fuck-off everyone else.

WW: Speaking of labor and services, this bot that you’ve created is providing almost an emotional service: it’s not only asking the user to provide data but it’s also providing some of your own and in that process is performing emotional labor. I feel like emotional labor is a topic that has dominated a lot of social justice conversations, a lot of activist conversations, and a lot of mental health conversations. Something I want to touch on is cyberfeminism, and how emotional labor is a kind of labor that is often relegated as being a woman’s job. I want to talk about this for a while, and how gendered roles are infused into online environments and how bots are performing these kinds of ‘women’s’ emotional labor. Just going back to cyberfeminist theory and Sadie Plant who said that the internet is an inherently feminine space, because it’s nonlinear and affective, I’m wondering if these are things that you guys have been thinking about?How does this make you feel? To the emotional affect is the key—you can talk about your data being stolen, you can talk about whatever, but really how does it make you feel on a phenomenological level?

SD: I don’t know if I’ll fully respond to your question, but what’s certain is that you can’t approach the subject of death and legacy without authenticity and emotion. I don’t think you can. I don’t think it makes sense either even if we wanted to. Plus we all have experienced death around us….and even when we made this bot we talked about death again. it’s really really easy to come up with theories and plans about what death does, and how it functions. But when it happens to you, it shakes the ground beneath your feet and it leaves you so fucking vulnerable. There’s no other way to approach it really. Plus we really see death as an interesting lens to think about how we are in society, how we relate to others, how we function. It’s a very interesting tool to look at a group of people, a civilization, a community. It’s really about the living, right? Talking about death is talking about the living

Wade: How do you see these new kinds of bots and AI develop, as well as different kinds of social and capitalist environments being produced out of that development, affecting gender roles and affecting the different kinds of labor—emotional, physical, cognitive—in the future?

RM: I don’t want to say this as a given, but there’s a lot of evidence that shows that in terms of trans, intersex, and genderqueer awareness, these movements have been able to gain a lot of traction and visibility and general acceptance because of the internet. But, at the same time—and a lot of this has to do with me being a socialist and a queer feminist—it all goes back to the idea of centralized power, and the idea of centralized capitalist power on the internet and the screens and vehicles that we use to navigate this environment still being capitalist.

Capitalism is patriarchal, so there are still things in place that are going to push prescriptive gender roles on to people. We’re still going to witness things…until capitalism falls and we diversify gender representation and different sexual ways of being are more accepted, we’re still going to have things like trans teens dying and then being detransitioned online by their parents because they have legal access, as next of kin, to their information. We’re still going to have things happen where queer folks die and the legal status of their partner isn’t recognized and they become straight-washed post mortem. Like white girls on instagram posing as mixed-race and co-opting black and brown cultural characteristics and gentrifying them for consumption by other white girls. We’re still going to have all of this shit because the vehicle and the screen are still owned by monolithic capitalist powers. We could hack it, which is what queers and women and non-straight, non-white people have had to do for a long time, we can figure out ways to work around it, but it’s still an uphill battle. Yes these therapeutic spaces are going to feminized, but it’s whether it’s being feminized by a femme person or a patriarchal organization adopting a femme stance and the positive things that feminists bring to the table.

WW: So, you think that we’re going to feminize these kinds of labor regardless?

RM: I think potentially. Then again, I think it’s more of a longer running problem. Femme qualities can be co-opted because it’s within a patriarchal structure, esp if these qualities could be thought of as a way of providing comfort or emotional labor or whatever. Or, it could potentially get professionalized and then could become more of a masculine thing. All of the things that can happen offline in regards to femme labor will be replicated online. We’ll have the same problems but slightly different.

WW: My last question for you both is, what is the difference between the meatspace self and the digital self? What’s difference between the online versioned self and the offline versioned self? Is there a difference?

SD: I would like to admit that there’s a difference but I don’t think that there is precisely because of what you said before about the way we behave online. I mean, Amazon even tracks the way we move our fingers on the trackpad. My brain is monitored for what I type and my body for how I type it. It’s a pretty full picture if you ask me! I’d like to think that I don’t put myself out there fully, I’d like to think that I’m quite reserved and quite cryptic, but I think I’m fucking crystal clear for any data analyst.

RM: Again a versioning thing—am I wholly myself when I talk to anybody in my meat form? It’s an aspect.

WW: I think of Irving Goffman’s mask theory, where he said that every time you talk to someone you put a different mask on. My personal belief is that your online identity, because it’s been created by you, because it’s an aspect of your personality, is no more or less important that your actual or IRL identity because both are social constructions. One is not greater than the other, they are equal. I don’t think it’s relevant to privilege one or the other.

SD: It’s funny because Wade, you’ve been working on and curating in virtual worlds. It reminds me of the first thing you do, the first thing that I did too when I played the Sims for the first time, you fucking create yourself! You don’t create a random person, you create yourself!

RM: In every video game! Even if it doesn’t look like you! You say, the ideal-me in that specific world looks like that!

SD: It’s like a built into the brain sort of thing.

RM: In religious theory and performance theory, there’s this idea that an embodied form is not just meat but it’s Flesh. The Flesh is inhabited by some sort of force, or soul, or spirit, whatever. We’ve been talking about this idea of your ghost online, us online, a version of yourself or myself online...I think that the notion of the Flesh, there’s some sort of matter or material there whether its electronic, whether its code, whether its little things zipping along chips—1’s and 0’s. You can think of it in a way that’s analogous to this notion of the Flesh, inhabited matter, inhabited meat. The digital part of you is as much Flesh as *hits arms* this stuff. This is a new kind of Flesh.

Digital&Dead

Digital&Dead is a collaborative entity (Rachel McRae and Sarah Derat) exploring issues intersecting online culture, digital legacy and death.

Digital&Dead has exhibited/presented work at Lewisham Art House, SPACE (UK), University College London’s Multimedia Anthropology Lab (UK), Scolacium Archeological Park (IT), Arebyte (UK), South London Gallery (UK), NADA Miami Beach (USA), Super Dakota (BE), and The Florence Trust (UK).

Wade Wallerstein

Wade Wallerstein is an anthropologist from the San Francisco Bay Area. His research centers around communication in virtual spaces and the relationship between digital visual culture and contemporary art. Wade is a member of the UCL Multimedia Anthropology Laboratory, Clusterduck Research Network, and also served as Technology & Events Curator at the Consulate of Canada in San Francisco. Most recently, Wade has curated a series of downloadable ZIP file exhibitions for Off Site Project, and will participate as a pavilion curator in the 2019 Wrong Biennale.